The fashion business frequently appears to be an endless loop of creations, applause, and consternation – a snake devouring its own tail, leaving many people perplexed… well, South African fashion is giving an ‘old’ world of fashion a new lease on life.

Fashion, particularly prêt-à-porter and couture, resembles an ethereal kind of art in many ways: it appears in shapes and textiles, patterns, and trends, only to vanish or be replaced a season later. It makes an appearance frequently and grandly at fashion weeks and events around the world, only to be followed by a flurry of photographs blasted over Instagram feeds and billboards, huge price tags dangling in front of our eyes like Ulysses’ sirens.

The problem is, that endless circle of fashion production, as pointless as it appeared, was developing at a steady rate year after year. Personal luxury items, luxury automobiles and hospitality, fine and wine spirits, gourmet food, fine art, high-quality design and furniture, private jets/yachts, and luxury cruises climbed to an anticipated €1.2 trillion in 2019, with favorable performance across all areas.

Pandemic Put the World Fashion to a Halt, but Not South African

Until early in 2024, when the world came to a halt, unmoving, with the pandemic’s hand slicing into the fashion loop with the accuracy of a pair of scissors cutting through silk. Things abruptly got frozen, as they did in many other businesses throughout the world: no more fashion weeks, no advertisements on billboards; the lethargic, almost flatlined pace turned fashion on its head, at least for a few months. Sustainability, more careful production, meaningful collections, and collaboration with local craftspeople became more prevalent themes.

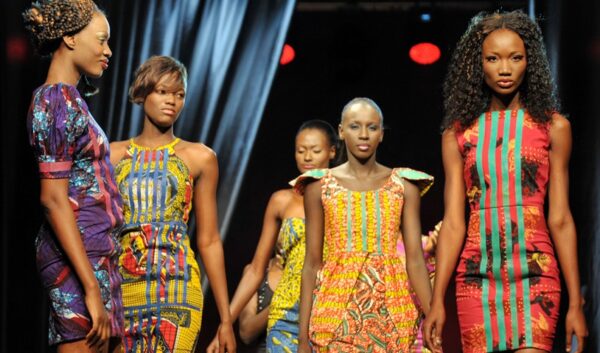

South African (and fellow African) designers are light years ahead of their Western counterparts in this sector, where fashion is obliged to adapt to its surroundings, to be more clever and insightful. Local designers’ collections are generally characterized by agility, originality, and a profound, almost emotional concern for presenting true tales via clothing. Having to design, promote, and sell their work with little support and little help from the government, with limited access to luxurious fabrics, and a Western market with better and more connected infrastructures, South African designers, artists, and creatives must rely on ingenuity and support from one another to move forward. And they are moving forward so we should be paying attention to them.

South African fashionistas take advantage of every opportunity to promote their pieces, doing it even on events that have nothing to do with fashion such as the World Sports Betting Cape Town MET 2024 at the end of January where labels like Ruff Tung were presented. No wonder there’s the connection between fashion and gambling in Africa given the latter is on the high rise on the continent, especially its online version that can be practiced e.g. on the best Tanzanian casino sites that can be found at TopCasinoExpert.Com.

There are two reasons why the terms “Africa” and “luxury” should be used together. The first is a new definition of luxury in the ongoing century. Consumers, particularly in the western world, are coming to value products that have been handled by human hands, and Africa’s handwork is exceptional. From the Tuareg’s work for Hermès to the bags made in Kenya for Ilaria Fendi, Stella McCartney, and Vivienne Westwood, African hands create beautiful products, often with the extra benefit of being ecological and ethical.

Standouts on the South African Fashion Scene

Take Thebe Magugu, for example. Since the launch of his eponymous brand in 2017, he has always explained how each of his collections is inspired by an almost anthropological approach to design, with societal commentary, economics, South Africa’s complex and rich heritage, and intimate stories stitched and printed into the garments. Check out “Genealogy”, the SS2024 collection based on old family photos produced by the young designer as a reminiscence of his 2016/17 collaboration with fellow designer Rich Mnisi, named “Family Photos”. The collection is laced with clever and meaningful design.

Sindiso Khumalo, another LVMH Prize winner, founded her eponymous line in 2015, focusing on modern sustainable textiles with a strong emphasis on African narrative. She’s a sustainable textile designer, Central St Martins graduate, and Cape Town-based. In fact, Khumalo uses watercolors and collages to design the fabrics in her collections by hand. Her silhouettes are feminine, powerful representations of black women from the turn of the century to the 1980s, with balloon sleeves on tailored wide-leg pants, barely-there frills enhancing the top of a blouse, and everywhere prints that evoke the rolling green hills and lush landscapes of KwaZulu-Natal, where Khumalo is originally from.

Lukhanyo Mdingi developed a collection that earned him the Karl Lagerfeld LVMH Prize in 2024. He meets with producers in the Karoo and works with weavers from Philani, a Cape Town-based NGO dedicated to improving child nutrition and empowering women from marginalized communities, to create incredible garments using local fabrics like mohair and wool, gold threads running through bright reds; he met with producers in the Karoo and worked with weavers from Philani, a Cape Town-based NGO dedicated to improving child nutrition and empowering women from marginalized communities.

Rich Mnisi, who’s recognized for his branded knitted jumpers and collections influenced by pop culture and modern South Africa, founded “Stories of Near”, a kind of club, a network of trailblazers transforming the African fashion landscape. The goal of the club is to create an ecosystem of stakeholders who share common values and goals.

Outside of South Africa

We should also keep an eye on Dazed editor Ib Kamara’s remarkable work outside of South Africa – the Sierra Leone-born and London-based stylist generates dramatic and inventive imagery that is changing fashion visuals.

Aurora James, the founder and creative director of Brother Vellies, is also the driving force behind “The Fifteen Percent Pledge”, a non-profit organization that invites major retailers and corporations to join (the organization) in creating sustainable and supportive ecosystems for black-owned businesses to succeed. She is the designer behind Alexandria Ocasio-MET Cortez’s Gala dress “Tax the Rich”.

Finally, Liya Kebede’s Lemlem, which she founded in 2007, focuses on hand-woven cotton garments that have been grown in Ethiopian fields since ancient times. Rather than huge growth at the expense of quality and craft, the label focuses on sustainability and controllable numbers and orders. This is the epitome of luxury.